Regardless of tenure, cybersecurity professionals in leadership positions receive limited training. Even those who have been in the profession the longest admit they have learned more from past experiences observing their managers, supervisors and leaders than they have through formal training opportunities, according to a recent member survey conducted by ISC2. Now, as they occupy their own positions of responsibility and leadership, the onus is on them to pass on what they have learned to their team members, shaping the next generation of cyber professionals and leaders.

Learning by observing is a long-established notion of knowledge transfer, a valuable tradition in any profession or trade. However, the limited formal training provided to leaders in a complex occupation with a high degree of responsibility, such as cybersecurity, raises these questions:

- Should this be the predominant path to positions of responsibility and leadership?

- Are cybersecurity professionals acquiring and perpetuating hard-to-break bad habits?

- How can the field continue to help more professionals advance to leadership roles without investing in formal training?

It is clear from the responses of professionals not in management (supervisors of teams) roles that they grapple with these questions. In responses to open-ended inquiries about leaders, participants indicated their leaders demonstrate limited or no skills in areas such as communication, strategic mindset and business acumen. Their perspectives are largely corroborated by the managers who answered the survey, which means many recognize their own leadership shortcomings. The survey polled 259 cybersecurity professionals, 48% of whom have formal leadership responsibilities (e.g., managing teams or departments) with another 41% having informal leadership responsibilities (e.g., senior professionals responsible for training or mentoring other team members).

Learning by Observing

It’s reasonable to expect cybersecurity leaders – and those on the path to leadership – to receive comprehensive formal training for their current and future jobs. They are, after all, working in a complex field fraught with operational, economic and reputational challenges.

However, less than two thirds (63%) of respondents said they’ve received such training. The overwhelming majority (81%) learn primarily through observing leaders. In addition, 86% said “experiences with previous supervisors, managers and executives in the private sector” shaped their “outlook on what makes a good leader.”

Formal training is more prevalent among formal leaders, with 77% saying they have received some. Still, 86% said they learned from observing leaders, while 86% noted that previous managers shaped their outlook on leadership. Among informal leaders, only 53% have had formal training, 80% learned from observing leaders, while 87% said experiences with leaders shaped their leadership perspective.

Respondents also said they learn about leadership from books, conferences, podcasts, webinars, as well as online and in-person instruction. More than half (59%) cited mentorships.

Types of Training

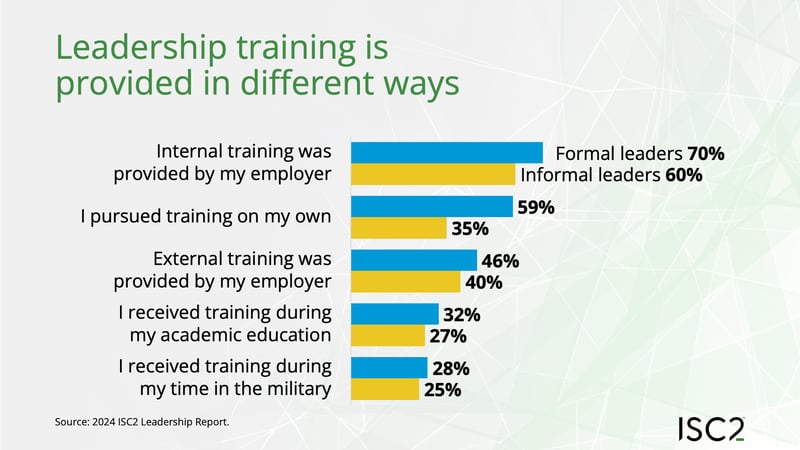

Cybersecurity training occurs in a variety of ways. The prevalent method, cited by 70% of formal leaders and 60% of informal leaders surveyed, is internal training provided by employers. That was followed by training that professionals pursue on their own (59% of formal leaders and 35% of informal leaders) and external training provided by employers (46% of formal leaders and 40% of informal leaders).

Military training, cited by 28% of formal leader respondents, along with academic education (32% of formal leaders) also play roles in leadership training. Not surprisingly, the survey shows a correlation between formal training and tenure. The longer cybersecurity professionals work in the field, the more training they receive. But no matter how long they’ve been in the field, their perspectives and leadership practices are shaped primarily by observing others.

Leadership Qualities

The fact cybersecurity managers and supervisors receive limited formal training does not escape notice from those they manage. They have clear ideas about what makes good leaders. They also notice their managers’ shortcomings.

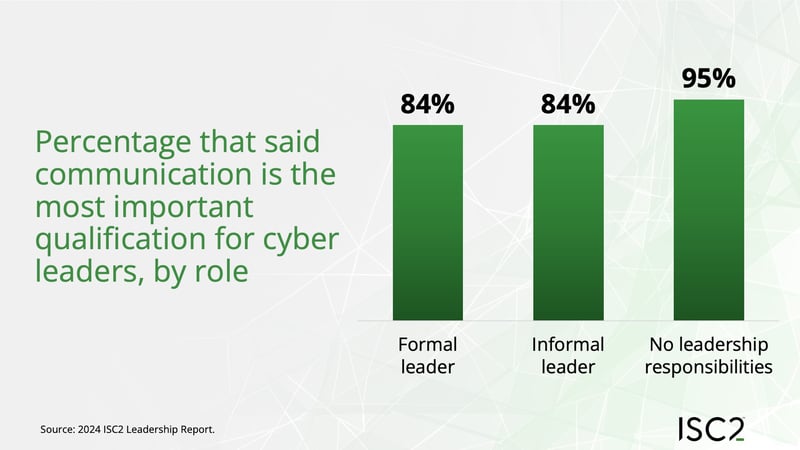

When asked what qualities they consider important in a leader, communication rises to the top, cited by 85% of all respondents. Strategic was a distant second, cited by 41% of respondents, followed by open-minded, technically skilled and decisiveness.

Among rank-and-file professionals, communication (85%) also tops the list, followed by open-minded, strategic, technically skilled and inspirational. For their part, managers answered in this order:

- Communication

- Strategic

- Technical skills

- Business acumen

- Open-minded

Leadership Shortcomings

Business acumen ranked surprisingly low as a leadership quality (32%) with managers and even more so among team members (13%). This suggests a failure to recognize the relationship of business acumen with communication, especially in interactions with the C-suite.

Poor communication, in fact, was the most common complaint in responses to open-ended questions about leadership mistakes. Consider this sampling of responses:

Not communicating with business management adequately.

Without in-depth communication with the business side, it is impossible to develop security goals that fully meet the business requirements.

Respondents also cited leadership mistakes such as working in silos and failing to explain priorities to team members. As one respondent put it: “Not communicating with the team especially when an incident happens.” The same respondent noted a “lack of business acumen to develop cybersecurity strategy.”

There were complaints about focusing too much on technology and too little on people, poor organizational structures and a lack of clear direction. Some other examples:

Disconnection from the impact of organizational/cultural shifts. Changes aren't always well received just because they're “the right thing to do.” We need to always work to understand and be understood by our stakeholders.

Too much red tape and overhead.

Seeing cybersecurity as an overhead until the inevitable happens.

Room for Growth

Respondents were asked to name skills they need to strengthen on their “path to a leadership” role. Communication and business acumen were frequent responses. Knowledge, strategic thinking and decisiveness also were mentioned. Here are some responses:

My communication skill. As it isn't just about talking shop, that shop talk needs to be translated both internally and externally.

Awareness of the struggles of those under me. It can be difficult to balance attention to those under you while managing a cybersecurity program.

Leading diverse working styles, being better able to shift workloads to the people who are best able to handle it, without overloading some who happen to be good at our largest problems.

Communication with different cultural backgrounds.

More hands-on experiences in broad roles. Cyber leaders need to understand every aspect, including the business, HR and other functions to fully understand how the risks affect each.

Key Takeaways

Despite the need for more formal training, the survey indicates cybersecurity professionals have a healthy degree of self-awareness, recognizing areas that need improvement. The following takeaways provide insights on which areas organizations should focus on for cybersecurity leadership training:

- Technical knowledge, though important, doesn’t cancel out other qualities, such as communication, strategic thinking and inclusiveness – a theme emphasized by ISC2 for many years.

- Although business acumen ranked low as a leadership quality, it isn’t being completely overlooked. Respondents see the need to articulate and translate complex cybersecurity matters to non-technical leaders.

- The emphasis respondents placed on open-mindedness underlines the complexity of cybersecurity issues. Creativity, diversity and analytical skills are required to understand problems and come up with solutions.

- Even managers recognize the importance of skills such as communication, strategic thinking and open-mindedness. Recognition is the first step toward correction.

Conclusion

The results suggest a need for more formal training. Allowing cybersecurity professionals to learn primarily by observing leaders may perpetuate bad habits, even if there is a side benefit of showing team members how not to act in positions of leadership. Organizations will be better prepared for cybersecurity risks if they institute comprehensive formal training.

To determine their needs in this area, organizations should review their training practices and poll their teams to identify areas needing improvement. Formal training, with an emphasis on skills such as communication and strategy, leads to a better organizational structure with properly defined roles. Ultimately, it creates a more robust cybersecurity posture.

ISC2 is offering a series of cyber leadership training opportunities that include formal training sessions, resources and an opportunity to share experiences within a cohort of professionals committed to cybersecurity leadership. Register now.

- Cybersecurity Leadership Skill-Builders from ISC2 help you gain key perspectives on cybersecurity and their real-world applications for executive- and board-level planning and decision-making

- ISC2 Executive Leadership Courses offer deeper-level learning, created by industry experts and available on demand

.png?h=1080&iar=0&w=1080)

.png?h=500&iar=0&w=500)