Fortra 2025 State of Cybersecurity Survey

Fortra knows that no one understands the threat landscape like the teams dealing with it every day. Take Fortra’s 2025 State of Cybersecurity Survey to share perspectives from your industry. Survey closes November 1, with results available in January. Help us improve the security landscape together.

Operational Technology Security

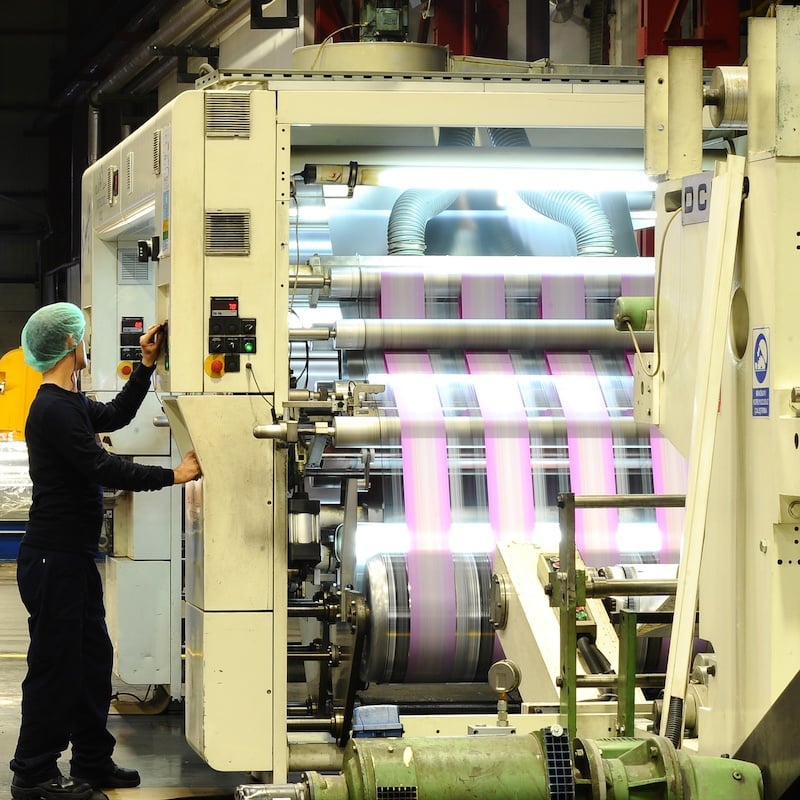

Operational Technology, or “OT”, is a concept that mainstream IT and cybersecurity teams aren’t necessarily very familiar with given the long-standing separation of the two. There are numerous definitions around the internet, many of which are either ambiguous or unintelligible, so let us paint a picture of what it means.

Defining IT should be straightforward for cybersecurity professionals: it’s servers, operating systems, printers, routers, switches, firewalls … all the systems that the IT department runs. That’s what OT isn’t. Now look at the machinery a business might have: boilers, air conditioning and heating units, generators, coal mine conveyor belts, pumping plants, machines that crimp caps onto beer bottles, hospital MRI scanners, the list is endless. Over time, the manufacturers of these types of equipment have produced technology that lets these traditionally standalone systems connect into the company network so they can be managed without having to walk up to the control panel. That connecting technology is what we call OT (and incidentally, the term is believed to have first been used in 2006, in a Gartner paper by analysts Bradley Williams, James Spiers, Zarko Sumic, Kristian Steenstrup).

Many of you reading this will have come across some other terms that relate to getting mechanical equipment connected to the network – SCADA, ICS, or DCS. If you’re wondering what the difference is between these and OT … simple: OT is the term we give to the family that these technologies fall into.

Unsurprisingly, if we are connecting something to the organization’s network, we need to secure it. In some ways it’s more critical to secure OT than IT: it’s unlikely that a piece of malware will make a server explode, of course, but an attack on, say, hospital equipment that delivers radiation therapy can have direct, fatal consequences. Yes, the knock-on effect of IT kit being attacked can bring physically harmful results downstream, but with OT there is the potential that the harm could well be direct.

A Term for the Times

You also need to consider that SCADA and ICS have been with us for many decades. The IEEE notes that the concept came about in the 1960s (though the term SCADA appeared a decade later). Nobody thought about security, because there were no security concerns: the internet was not yet around, so the risk of a remote attack was not considered because it simply didn’t exist. Of course, as the internet became mainstream from the late 1990s onwards, it was inevitable that people would want to be able to manage their OT via this flexible, relatively inexpensive and increasingly ubiquitous network.

The problem is clear: taking something that didn’t have security designed into it and connecting it to the internet is a highly undesirable thing to do. It would be unfair to blame the designers of the SCADA and ICS equipment: they could never contemplate mitigating a risk that would not exist for another 20 years thanks to technology that even the world’s best futurologists would have found far-fetched.

Wind the clock forward to 2024 and, of course, the designers of today’s OT give far more though to the security elements of what they are producing. Just as with IT, this doesn’t mean we can just say: “ah, that’s fine then” and stop worrying.

Legacy Equipment and Modern Security

First, we need to consider that although designers of modern OT have security in mind, much of our OT may be much older. The systems IT managers run tend to have a lifetime of five or six years, sometimes less, which means that it is replaced with something newer (and whose design considerations are current) much more quickly than technology connected with OT, where lifespan might be measured in decades. Worse, long-serving equipment may mean obsolete operating systems – X-ray machines run by PCs running Windows XP, for example – which guarantees vulnerability. For such systems, where it is not possible to apply security on the devices themselves, the answer is to apply heavy restrictions around them: access control lists in network routers and firewalls between them and the rest of the network.

Second, we need to make sure that the OT’s software – and by implication its security features – are kept up to date. This throws up an interesting dilemma: who is responsible for doing that? In the cybersecurity team we are used to having a close relationship with the IT department, particularly when it comes to ensuring systems are patched and working with them to deal with other vulnerabilities that our cyber tools identify. With OT we now need to have a similar relationship with the people who manage the equipment that the OT is connecting into the network. The best people to update the OT are those who manage the hardware – after all, there is every chance that systems will need to be closed down in order to do the updates and they are the ones who know how to do this safely and who can work with their business users to agree downtime.

On this last point, there is a potential problem: downtime on industrial systems can be highly unpopular, because it can be very costly, and so the cyber team’s request for downtime to have updates applied may well be declined. There are two options here. First is to work with the maintenance team to explore whether there are already downtime windows that could be used to do OT security updates: after all, the majority of machinery needs some kind of regular maintenance. If that approach is not available: you’re back to our first point from a few sentences ago, and you need to wrap extra security around the OT which won’t need machinery downtime when you come to update it.

Third, we have a key difference between IT and OT. If we want to defend our IT systems we install anti-malware software, vulnerability scanning agents, EDR endpoint apps and the like. There is a very good chance that much of your OT will either run a proprietary operating system, in which case there won’t be an agent you can install on it, or that it’s provided as an appliance (so the vendor won’t let you tamper with it and install agent software anyway). If it’s particularly proprietary then the vendor of your average malware or vulnerability software won’t know anything about how that piece of kit could be vulnerable anyhow.

Integrating OT into Reporting

Finally comes the key activity that we in cybersecurity do vast amounts of: reporting. We are used to reporting on IT systems: we need to make sure we report on everything that is connected to the organization’s network. Rather than using IT systems that we’re used to using – Active Directory reporting, the management console of the anti-malware product and the like – take a more holistic view. AD reporting will only tell you about anything that is integrated with AD. Similar logic applies to the anti-malware console. Use a discovery tool to crawl over the network and find everything. Pull data from the network switches about what is connected to what port. Have a word with a friendly coder or Excel expert and cross-reference everything until you’re confident you know of everything that is connected. Implement your security tools on everything they will work with. Be meticulous about producing a list of what remains, along with recommendations of what could be done about their security.

Bringing OT into your cyber reporting will give senior management a review of the types of risk that most management teams probably don’t have. It will mean they are aware that the risks exist and are in a position to decide what to ask you and the OT support teams do about them.

- Read more in this article looking at cybersecurity’s shift from IT to OT

- ISC2 Security Operations Skill-Builders include courses on OT, including Cybersecurity in Industrial Control Systems

- ISC2 Zero Trust courses provide learning options for implementing Zero Trust to protect OT and IT systems